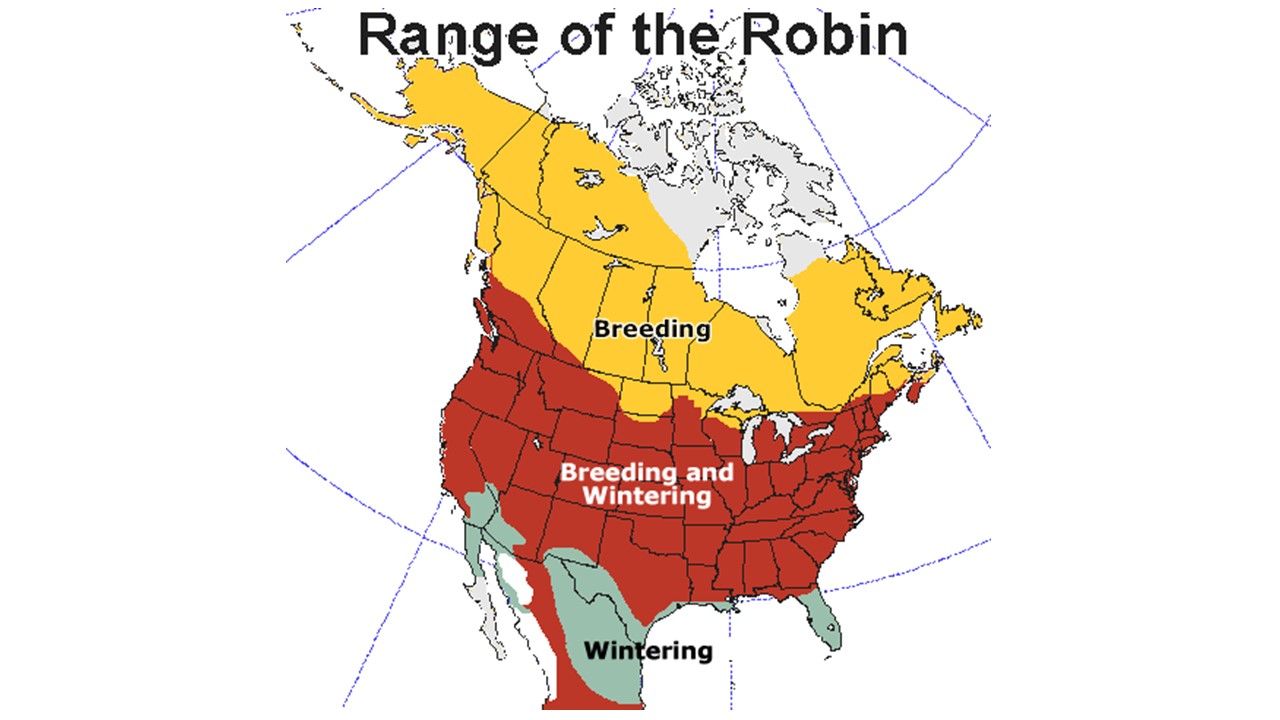

American Robins are considered short-distance migrants, which means they do not embark on the epic journeys that some birds undertake. In the northern parts of North America, where they breed during the warmer months, robins often migrate southward as winter approaches. The migration itself can vary in timing and distance. Robins might travel a few hundred miles or even just a short distance south to find milder weather and more available food. As the weather gets colder and food becomes scarcer in their breeding grounds, those who choose to migrate south. They tend to travel during the day and might fly in loose flocks, stopping to rest and refuel along the way.

As winter wanes and spring begins, robins that migrated south begin their return journey northward. This migration, known as spring migration, is driven by the changing seasons and the availability of insects, which are a crucial part of their diet. Robins fly at around 30 - 36 mph during migration and can cover a daily distance of approximately 100-200 miles per day in favorable conditions. Robins primarily migrate during the daytime, using the sun's angle and adapting to weather patterns for navigation. Some have been known to occasionally travel at night. Weather conditions, including storms and extreme temperatures, and land use can influence migration success. Studies indicate that only around 25% of fledging robins survive until November. Experienced adults also face mortality during migration. In summary, the American Robin's migration is a complex and dynamic process, influenced by environmental factors, food availability, and seasonal changes. Their adaptability and ability to form flocks contribute to their survival during migration and wintering.

The Journey North American Robin Migration Project was launched in 1996. As with other Journey North projects, the American Robin Migration Project initially focused on tracking spring arrival dates by asking volunteers to report when they first saw and heard American Robins. In 2012, Journey North opened this project to year-round monitoring effort. Studying the migration of American robins is crucial for several scientific reasons, and some researchers even refer to them as "nature's engineers" due to their significant impact on ecosystems. As bioindicators, their migration patterns can reflect environmental health, offering insights into shifts in climate, food availability, and habitat conditions. Tracking these patterns helps researchers understand how climate change affects bird behavior, such as changes in migration timing due to warmer temperatures. Robins play a key role in ecosystems as predators and prey, controlling insect populations, aerating the soil, and dispersing seeds, promoting plant diversity and healthy soil dynamics. This knowledge is vital for conservation efforts, as it identifies critical habitats along their migratory routes that need protection. Research into robin migration also reveals their adaptability and resilience in response to environmental changes. Furthermore, robins' familiarity with the public makes them excellent for engaging in participatory science projects, raising awareness about environmental issues, and encouraging public participation in conservation. Overall, studying American Robin migration enhances our understanding of environmental health, climate change, and ecosystem dynamics, while fostering public engagement and driving technological innovation in wildlife research.

- Spring Migration

Robins migrate from northern breeding grounds to southern regions as winter approaches. Driven by the availability of food, they might travel a few hundred miles during the day. Robins initiate their spring migration as the days lengthen, experiencing zugunruhe or migratory restlessness. They start moving northward from Florida and the Gulf states, tracking the 37-degree average daily isotherm. Males typically follow this migration pattern, arriving on breeding grounds a few days to two weeks before females.

- Breeding and Nesting

Upon arrival, male robins engage in territory establishment, marked by singing and territorial battles. Females join later, focusing on nest building and laying eggs. The female's nesting duties include incubation, while the male defends the territory and contributes to feeding. Breeding occurs in the northern parts of North America during spring and summer. Nests are often built in trees, shrubs, or even on human-made structures.

- Preferred Habitat

Robins are adaptable and can be found in a variety of habitats, including gardens, parks, and woodlands. Robins prefer diverse habitats, ranging from lawns and open fields for foraging to thick coniferous trees for shelter during inclement weather. Their adaptability allows them to thrive in various environments.

- Fall Migration

Some robins migrate south for the winter, while others stay put, depending on food availability. As winter approaches, robins face diminishing insect and worm supplies. The ground freezes, making it challenging to find their preferred food sources. In response, they switch to a diet of fruit. Fall migration sees robins forming loose flocks for both feeding and flying. Some robins undertake extensive migrations, covering thousands of miles.